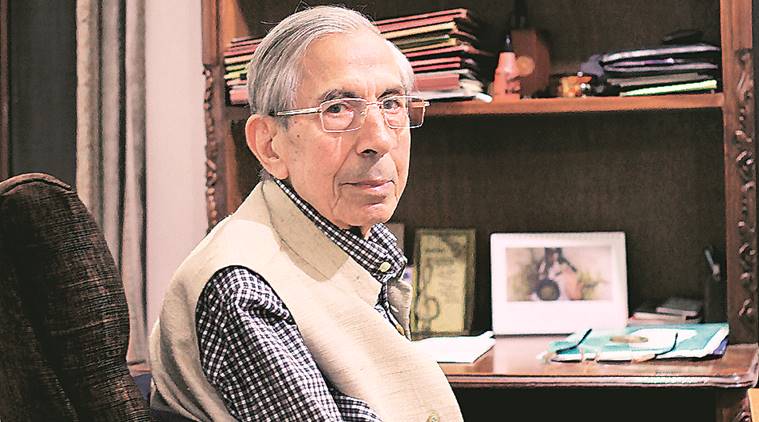

He probably had a large hat rack. Other than the visible khaki, Ved Marwah wore hats of different hues and shapes with equal ease and élan. Their diversity and dignity will remain etched in the eyes of his colleagues, collaborators, admirers and friends.

Along with innumerable women’s groups, researchers, activists, artists and filmmakers, I had the good fortune of experiencing the holistic design and creativity of his feminist vision, worn suitably with his just get-it-done hat.

Around April 1983, a joint secretary was appointed to what was then the Ministry of Social Welfare. One might have expected a lady IAS officer. But the job was assigned to a male police officer and this soon revealed itself to be a great piece of lateral creative thinking. Here was a joint secretary who clearly understood that women’s lives matter at a time when widespread dowry deaths and other forms of violence against women were being reported.

There was palpable anger and energy among women and we were seeking immediate remedies. Not everyone was on the same page. No easy assignment for Marwah.

One to build bridges, he opened the doors of his sixth-floor office, welcoming, even inviting, women of all hues who were engaged with “women’s issues”. You would meet Mohini Giri, Vina Mazumdar, Devaki Jain, Rami Chhabra, Zarina Bhatty, Gauri Choudhary and other pioneers of what came to be called the second women’s movement of India.

Marwah’s team, S Y Quraishi and Vina Kohli, were much like him — in listening mode. Together, they sought to deepen their understanding of women’s points of view. Gradually, trust was built. Productive partnerships formed, and collaborative ventures became possible.

The lines between state and society began to blur. At times, one might cheekily but gently even request his guidance as to which streets were best suited for dharnas and protest marches. These open doors resulted in mutual enrichment.

In late 1985, Marwah moved from the women’s department in the ministry to the police headquarters as commissioner of police, Delhi, but not forgetting his feminist hat, now an intrinsic part of his personality. The Delhi government had set up the crimes against women cell before he joined, in 1983. The dynamic police officer Kanwaljit Deol described it as “the first police response directed specifically for women in India, and in all likelihood, through the world”.

On joining the headquarters, one of Marwah’s first self-appointed tasks, along with his now staff officer, Deol, was to meet the then Home Minister Buta Singh for immediate funds.

“When he asked for something, he got it immediately,” recalls Deol. Overnight, the 10 vehicles at the disposal of Delhi police grew to 200 new Gypsy vans. A single helpline with the women’s cell multiplied into 100 helplines. As its mandate grew, based on the needs of women survivors, the Crimes against Women Cell swelled to 86 in nine districts of Delhi, “manned” by Deol. Only a powerful leader like Marwah could make this possible, she recalls.